click icons for more info

Mexico City

Santiago Mota (MDE + MDes E&E ‘20)

There are 318 traditional markets in Mexico City with 77 thousand stores and half a million families dedicated to them. Located in the center of the urban life, both physically and metaphorically, these markets receive the fresh fruits and vegetables from the Mezquital Valley everyday through a gordian knot that includes farmer bodies, vegetable boxes, diesel-driven trucks, large-scale logistical networks and food supply chains.

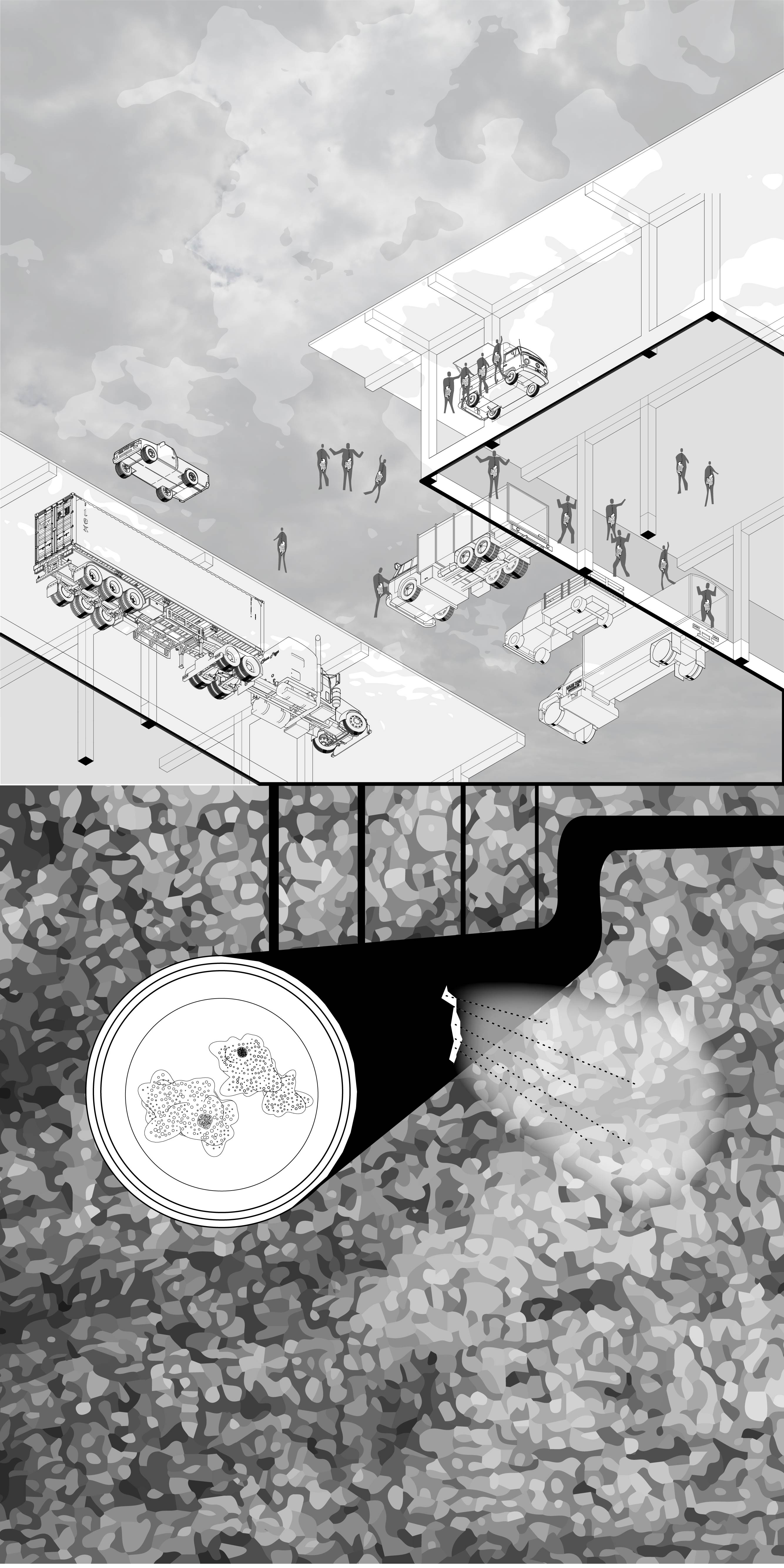

The Central de Abastos, the pinnacle of this bundle of machines, human bodies and vegetables, is one of the largest food supply markets in the world. Fresh produce from different places, including the Mezquital, arrive in trucks and flows through this building for distribution into one of the 300+ local markets and 1000+ produce shops in the city. And at the back-end of this market of markets, lies a generic space that is replicated at different scales but with the same programmatic function throughout the city, and most importantly, the same flexibility. Here, the scale of the truck, the kiosk, the box and the vegetable match (Figure 1).

A truck fully packed with onion, lettuce or radish is redeployed into a component of the market, a space that addresses the transformation of produce from the ground to the tables, but also the transformation of pathogenic lifeforms within the vegetables and fruits. A kiosk and a food vending spot, sometimes side by side, sometimes one and the same (Figure 2).

Entamoeba histolytica thrives here. It is not able to move alone, as it relies on motorized vehicles, human labor, edible transports and plastic containers. As one of the first agents defined as a pathogenic and efforts for developing a microscope for epidemiological purposes were driven by the connection of this protozoan with human urban agglomerations and outbreaks of dysentery. Humans are regarded as the definitive host of this invasive species as it has co-evolved for thousands of years with humans and today there are no other meaningful reservoirs.

Entamoeba histolytica has developed a deadly strategy, quietly occupying some human bodies while shedding a geometric number of robust cysts in feces, which are immediately infective. These asymptomatic carriers, especially food handlers, commonly contribute to the spread of disease, as chronic cases and asymptomatic carriers can shed up to 1.5 billion cysts daily. Cysts can be present in sewage and contaminated water, and survive for long periods in aquatic environments while transmission can occur through food and water contaminated by human feces. Cysts are resistant to chlorine at levels used in drinking water supplies, rendering primary disinfection of the majority of drinking water supplies ineffective.

Figure 3: Conceptual tracing back and forth from the Mezquital into Mexico City’s markets through large-scale logistical networks and food supply chains.

Mexico City is fed with what it excretes. To make visible the direct relation between wastewater irrigation in the Mezquital Valley, the production of edible fruits and vegetables and the distribution of this edibles into Mexico City markets and human bodies we need to trace the path back and forth from the Mezquital into Mexico City’s markets. (Figure 3)

Mezquital

Chelsea Kashan (MLA ‘21)

Farmers working in the Mezquital Valley region of Mexico, are dependent on wastewater provided by Mexico City. An accumulation of pipe systems and a difference in sea level of about 400 + meters carries wastewater from drains and sewage systems in Mexico City to the crop fields in the valley, which run in controlled soil irrigation trenches alongside plots. The farmers profit on Mexico City’s waste, a system that has been in place for over 100 years. The introduction of the government sponsored (CONAGUA) wastewater treatment plant, Atotonilco, poses a threat to farmer livelihood; farmers claim that reducing the nutrients attributed to unfiltered waste, would reduce their crop yield and overall cash earlings. The introduction of Atotonilco has caused a great debate between those working in the Mezquital and health authorities. Health authorities, contrastly claim that using unfiltered wastewater poses major health threats due to the many bacteria that can survive and travel with the waste and have the ability to enter the food market and digestive systems. Epidemiological soils of the Mezquital Valley takes a close look at the actions of the farmer, the body as it moves along site, and the resulting proximity to a variety of pathogens (Figure 1).

As defined by the CDC, Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states and events in specified populations. The patient is the community, viewed collectively. To understand the farmers as a collective who are willing to face the threat of disease for maximizing livelihood, profit and tradition, we had to zoom-in to the scale of the bacteria, to understand its morphology, its relation to plant and soil, and to understand the closed loop relationship pathogens have between the Mezquital Valley and Mexico City.

Wastewater is the output of the digestive system, a system that carries both productive nutrient loads and harmful bacteria. We focus our attention on a few of the pathogens of concern in this region: Ascaris Lumbricoides (soil transmitted helminths), Vibrio Cholerae (Cholera), Salmonella Typhi (Typhoid Fever), and Entamoeba Histolytica (Amoeba). These four characters are able to withstand water conditions and have a life beyond when placed on vegetables via irrigation and, when in the uppermost meter of a soil horizon. Vegetables that are eaten raw, hands and the nose are the three most likely characters to transfer these pathogens from the exterior world (crops, soil and dust) to the interior (the digestive tract and bloodstream), where they pose their greatest threat. Framers and their families, who have direct contact with the soil, the water and the raw vegetables face the greatest risk of exposure, but it does not end here; a portion of these vegetables are brought back to markets in Mexico City where the pathogens that traveled attached to the vegetables can reunite with urban digestive tracts and re-enter the wastewater pipe system.

Figure 1: Farmers picking vegetables grown in the Mezquital Valley, using wastewater rinsing practices and loading the vegetables into trucks before transportation to Mexico City. (Source: https://www.inforural.com.mx/cloaca-da-vida-a-hortalizas/)

Figure 1: Farmers picking vegetables grown in the Mezquital Valley, using wastewater rinsing practices and loading the vegetables into trucks before transportation to Mexico City. (Source: https://www.inforural.com.mx/cloaca-da-vida-a-hortalizas/)Irrigation district 100-Alfajayucan, in the state of Hidalgo, primarily relies on untreated wastewater irrigation (1) and is the region approved for crop growth of vegetables that are primarily eaten raw, such as lettuce, radish, carrot, and onion. Framers wear boots to prevent water’s contact on the feet. Their hands come into contact with the soil and water, hands feed the mouth, children play in soil and lick their fingers, vegetables with deep wounds not carefully washed are eaten, soil dust gets inhaled: these are all ways in which the bacteria living in soil, attached to vegetable leaves or roots and in the air, can enter the body. The Ascaris Lumbricoides, for example, can enter the human body by inhaling the eggs present in moving soil dust, through children’s hands that come into contact with the soil or by eating infected vegetables that are not carefully washed or boiled. The worm hatches and grows in the human body, where it ultimately lays new eggs in the digestive tract. When released back into the sewage system, the cycle repeats. Not only is this process in loop, but many of these bacteria favor the climatic conditions in the region and can live in the soil for several months and even years (2).

Figure 2: Magnified image of a bacterial community embedded in a soil matrix, visible through scanning electron microscopy and dyes. (Source: https://www.mpipz.mpg.de/4713649/pr_hacquard_2018_11)

Soil is not static, it is a system and accumulation of matter, always exchanging. Understanding soil, and the conditions around it, such as temperature, moisture capacity, pH levels and compaction, allow us to see what other forms of life are capable of inhibiting it, besides our vegetables (Figure 2). These other life forms that inhabit the soil may not be visible, but have a lasting impact that affects human species at large. Understanding our relationship to the soil, and its other inhabitants, can help us make decisions about how we can safely interact with the land. Safe practices such as the use of gloves, or localized, small scale interventions that promote an awareness of the threat of pathogens, may help farmers safely continue using wastewater irrigation. Vegetables are not detached from their soil, they are one until the vegetable is met with clean water. When we consume vegetables, we are nearly consuming its soil, the very character that enables its growth. Our proximity to the soil must be taken with both caution and immense appreciation.

1 Humberto Romero-Alvarez, “Case Study VII* - The Mezquital Valley, Mexico,” WHO, https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/resourcesquality/wpccasestudy7.pdf

2 Ascariasis - What Causes Ascariasis? How Does Ascariasis Spread?, Sandra Gomez Gompf and John P. Cunha, https://www.emedicinehealth.com/ascariasis/article_em.htm#what_causes_ascariasis_how_does_ascariasis_spread