click icons for more info

Mexico City

Eric Van Dreason

In 2007, a year after he was elected the President of Mexico, Felipe Calderón gave a speech in which he painted a vivid portrait of a long-standing problem the country faced, a problem he as president felt a moral imperative to address. He described a scene in which he saw the children of the Endhó Dam in the Tula River Basin with red eyes, “infected.” Their sickness came from what Calderón described as pollution running through the wastewater that flows to the Mezquital Valley from Mexico City, pollution that had been allowed to run its course for “decades, perhaps centuries.” Calderon’s stated goal was put simply: he implored his audience to put faith in a solution that could reverse this damage.

Thus, a private-public partnership was born to pursue the construction of a wastewater treatment plant at Atotonilco. In a design-build-operate-transfer agreement, The Treated Water of the Valley of Mexico consortium (or Aguas Tratadas del Valle de Mexico, aka ATVM) formed after winning an international bidding contest for the contract provided by the Comisión Nacional del Agua, or CONAGUA, the Mexican National Water Commission, in 2009. ATVM fronted 20% of the total cost of the project, while Mexico’s national development fund, FONADIN, subsidized 49% of the project, with the remaining falling to commercial investment banks.

Composed of a number of private companies, the majority stakeholder in the ATVM consortium (with a 51% equity interest) is IDEAL, an infrastructure company led by the Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim. Slim has built his fortune through acquiring and selling a diverse set of assets, but his most precipitous windfall came when the Mexican government privatized its telecommunications company Telmex in the 1990s, allowing Slim to buy a controlling stake. Through successive investments in telecommunications infrastructure across the country, Slim was able to insulate himself from competitors, charging upstarts exorbitant fees for the use of the company’s extensive network. Though the Mexican government has since attempted to rein in such practices, it's clear in cases like Atotonilco that it’s not so easy for the country to extricate itself from a wealthy investor like Slim entirely, though the social cost of such a strategy remains incalculable.

Calderon cited other reasons to focus his country’s attention upon this problem. The issue affected Mexico City directly, where inhabitants source much of their drinking water from groundwater sources below. The consumption of water outpaces natural groundwater recharge, causing several effects, including differential land subsidence, occur across the metropolitan region.

In all of this, who or what remains unspoken? Most noticeably, farmers of the Mezquital Valley, who were granted the right by presidential decree over a century ago to irrigate their croplands with wastewater from the capital, were given no real space to contribute to discussion of Atotonilco. Soon, the farmers fear, they will be paying to fertilize their fields to produce lower yields of their crops, when previously the nutrient-rich water from Mexico City was provided at no cost. While the health risks presented by contaminated soil may have been prioritized (at least rhetorically) by state actors, what is to be made of the impending risk of poverty faced by the 700,000 farmers of the Tula Valley whose livelihoods are at stake?

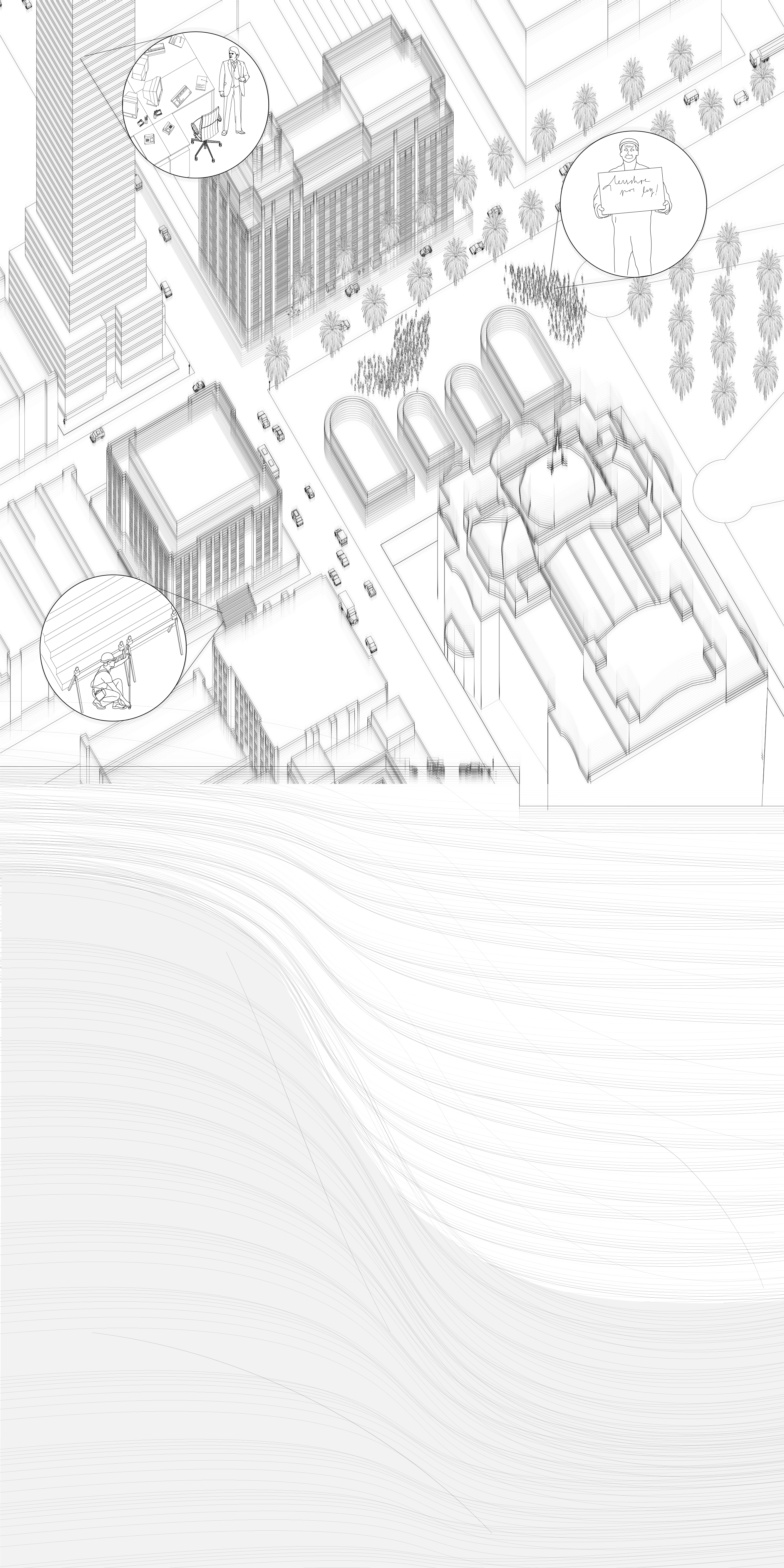

Mexico City is where all the forces described above come together, sometimes within the view of a single intersection. The Palacio de Bellas Artes sinks into the ground, meters at a time, while the building across from it rises higher due to fault lines and subsidence. The Torre Latinoamericana, one of the tallest skyscrapers in Mexico City, again marks the presence of Carlos Slim, whose businesses operate on seven of the 44 floors of the building. Protestors from the Mezquital come here to protest, perhaps to remind the capital of their existence. The complicated nature of Atotonilco is perhaps, in part, represented by the hum of the everyday within the city – the protestors join the throngs of people on the streets while the board meetings of shareholders carry on, agreements signed, money promised and delivered into electronic wallets and pocketbooks, the files placed in their respective folders and tucked away in the vast sea of paperwork and bureaucracy. It’s this minutiae that gave rise to one of the most expensive infrastructural projects the country has ever seen, and yet for most of the city’s millions of inhabitants, it’s out of view, humming along in the background. It’s business as usual, and perhaps that’s the problem.

“Presentación del programa de sustentabilidad hídrica de la cuenca del valle de méxico, en el salón Adolfo López Mateos de Los Pinos en la Ciudad de México, el 8 de Noviembre de 2007” (2012). http://www.conagua.gob.mx/conagua07/contenido/Documentos/MEMORIAS%20DOCUMENTALES/Memoria%20Documental%20Planta%20de%20tratamiento%20de%20agus%20residuales%20de%20Atotonilco.pdf

World Bank, Wastewater: From Waste to Resource - The Case of Atotonilco de Tula, Mexico (World Bank, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1596/29493.

“IDEAL Annual Report 2017,” Annual Report (IDEAL (Impulsora del Desarrollo y el Empleo en América Latina), 2017), https://www.ideal.com.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Annual-Report-IDEAL-2017.pdf.

Christina Siebe, “Human Impact on Geospheric Processes in the Critical Zone Exempli Ed by the Regional Water Exchange Between the Mexico City Metropolitan Area and the Mezquital Valley,” n.d., 17.

Rebecca Blackwell, “Campesinos Del Valle Del Mezquital Insisten En Usar Aguas Residuales,” The Associated Press Archive, Abril 2017.

Mezquital

Michael Cafiero

Every droplet of water that reaches the soil of Mexico City funnels through a single pipe and into the adjacent Mezquital Valley. Saturated with feces, metals, medications, and pathogens, the liquid is directed to irrigate nearly 100,000 hectares of farmland that in turn feed Mexico City. So why in November 2018 did hundreds of farmers begin to protest against the opening of one of the largest wastewater treatment plants in the world? Surely the prevention of lethal water from entering the agricultural system and back into the bodies of 20 million inhabitants must have been a sound and exigent solution. Felipe Calderon, the active President at the time, made promises of growing higher value crops like lettuce and tomato, clean drinking water, more agricultural land for a growing city, and most importantly the protection of public health. Atotonilco had become the paradigm of wastewater treatment plants and the panacea for the problem of the Mezquital.

The colossal anaerobic digesters at the treatment plant use thermal energy and microbial growth to treat the water - killing pathogens and sequestering heavy metals within sludge that is then dehydrated and discarded. However, Felipe Calderon’s vision of Atotonilco is an embodiment of the same processes that occur within the soil of the Mezquital. This dehydrated sludge is the same organic matter that farmers rely on to fertilize their crops. Without this free fertilizer, farmers’ yields would decrease by more than one third. Under the fields of the Mezquital, there is a circular economy of energy. Microbial growth and plant roots break down organic matter within the soil and produce energy to feed millions of people. In addition, many contaminants are reduced within the Valley itself. Before its arrival to the fields, the wastewater is exposed to ultraviolet light, reducing pathogens in the water. Perhaps the most critical similarity in this self-treating system is the soil’s ability to bind with or adsorb heavy metals in a process called cation exchange. Negatively charged clay particles attract positively charged metals, which inhibits plant uptake of them. These clay surfaces also bind with plasmids that carry antibiotic resistant genes. Cristina Siebe, a soil scientist working in the Valley, estimates that the clay has about 100 years until it reaches its adsorption capacity. However, the treated water from Atotonilco sans organic matter has gruesome implications to the soil. Once in the soil, the water decreases negatively charged binding sites and thus releases heavy metals. Genetic material from antibiotic resistant microbes are then shared again as heavy metal resistance genes. This situation not only allows plants to uptake heavy metals but also produces super-microbes that are resistant to contemporary medicine. Downstream of the watershed, the treated water - ridden with conventional fertilizers, heavy metals and antibiotic resistant bacteria - would travel through to Mezquital’s drinking water sources and eventually to the valley’s drainage outlet: the Gulf of Mexico.

The straightforward solution set forth by Calderon failed to see the incredible effects of wastewater treatment on exactly what it sought to solve: public health. To the farmer, wastewater was never a liability, but as a wealth of resources that had fed Mexico City for years. Wastewater is their livelihood. Without free fertilization, farmers would need to purchase conventional fertilizer. In Mexico, land prices are tied to what you can borrow from the bank. If farmers were forced to buy fertilizer, their land value would decrease and make it harder to borrow - creating a nearly impossible feedback loop. Just like the potential health effects of antibiotic resistant pathogens and exposure to heavy metals, poverty too takes the form of disease.

It is the soil itself that begins to reveal the expansive invisible threads that make it impossible to deem wastewater agriculture “good” or “bad.” There is nothing unequivocal in the case of the Mezquital. To really see the Valley, one has to understand the complex characters, processes and interconnections that lie beneath the surface and realize that one actually cannot untangle them. This eulogized billion dollar investment is merely a myopic, solution to the complex issue of public health. Disease is not borne from the Mezquital; rather, it is itself a symptom of the way in which we treat the environment.

World Bank. 2018. Wastewater : from waste to resource - the Case of Atotonilco de Tula, Mexico (English). From Waste to Resource. Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/922441521175520658/Wastewater-from-waste-to-resource-the-Case-of-Atotonilco-de-Tula-Mexico

Siebe, Christina. “Nutrient Inputs to Soils and Their Uptake by Alfalfa through Long-Term Irrigation with Untreated Sewage Effluent in Mexico.” Soil Use and Management 14, no. 2 (1998): 119–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.1998.tb00628.x.

Baker-Austin, Craig, Meredith S. Wright, Ramunas Stepanauskas, and J. V. McArthur. “Co-Selection of Antibiotic and Metal Resistance.” Trends in Microbiology 14, no. 4 (April 1, 2006): 176–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2006.02.006.